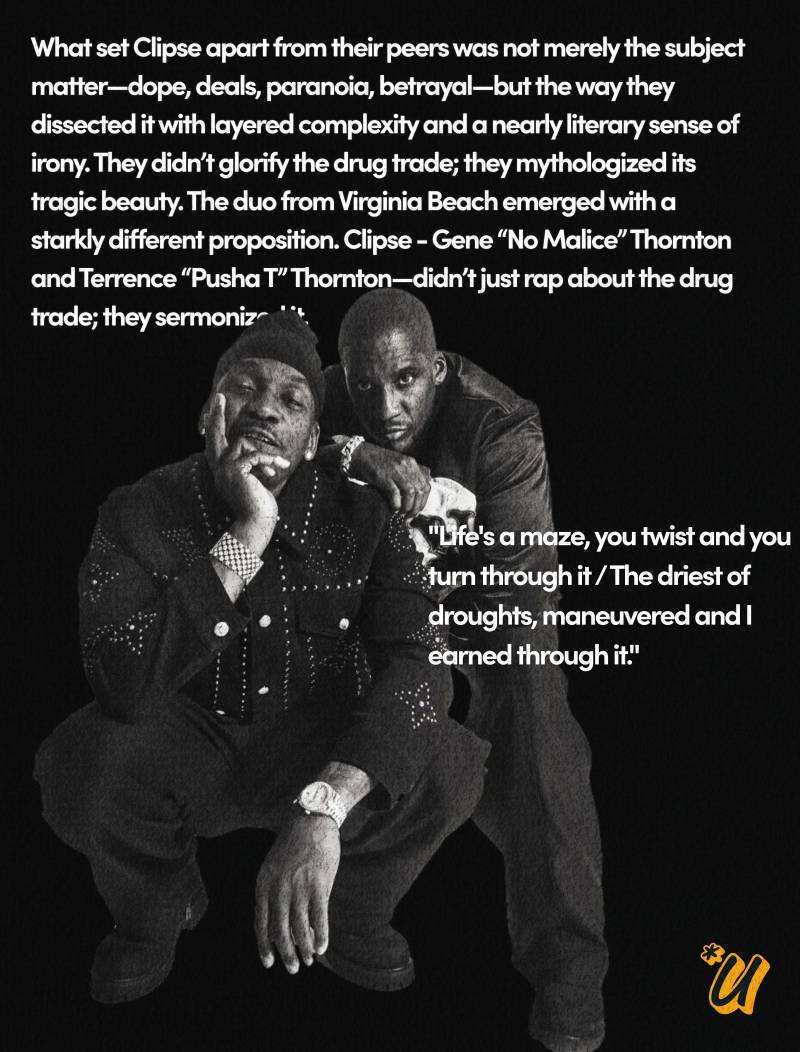

In the early 2000s, amidst the glossy sheen of commercial rap's platinum era, a duo from Virginia Beach emerged with a starkly different proposition. Clipse—comprised of brothers Gene “No Malice” Thornton and Terrence “Pusha T” Thornton—didn’t just rap about the drug trade; they sermonized it. With surgical precision, haunting production, and an unwavering moral tension, Clipse delivered some of the most potent, poetic, and unflinchingly raw street narratives hip-hop had ever encountered. Their arrival was not merely timely; it was transformative. Before Lord Willin’ (2002) even hit the shelves, Clipse had already been ushered into the spotlight by none other than Pharrell Williams, one-half of the production juggernaut The Neptunes and a fellow Virginia native.

The Neptunes’ sonic minimalism—brittle snares, icy synths, and negative space that felt oppressive in the best way—was the perfect canvas for Clipse’s stark worldview. “The way we approached Grindin’ was anti-radio,” Pharrell once told Complex. “It was deliberately skeletal. We wanted the lyrics to slap you.” Slap they did. Grindin’, with its DIY lunch-table beat and surgical imagery, became a cultural anthem. But beyond its commercial success, the track signaled a seismic shift in the tone and texture of mainstream rap. Gone were the lush soul samples or over-polished club beats. In their place: stark minimalism and clinical menace.

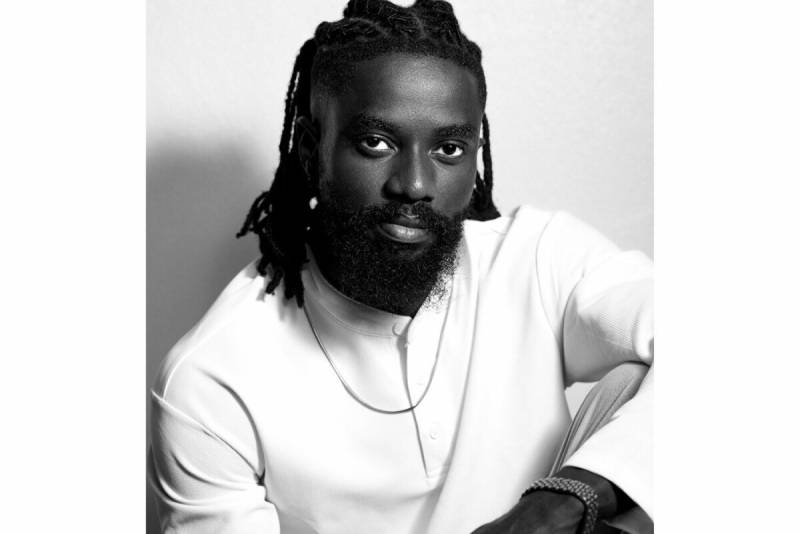

Clipse & Pharrell - 'Let God Sort Em Out'

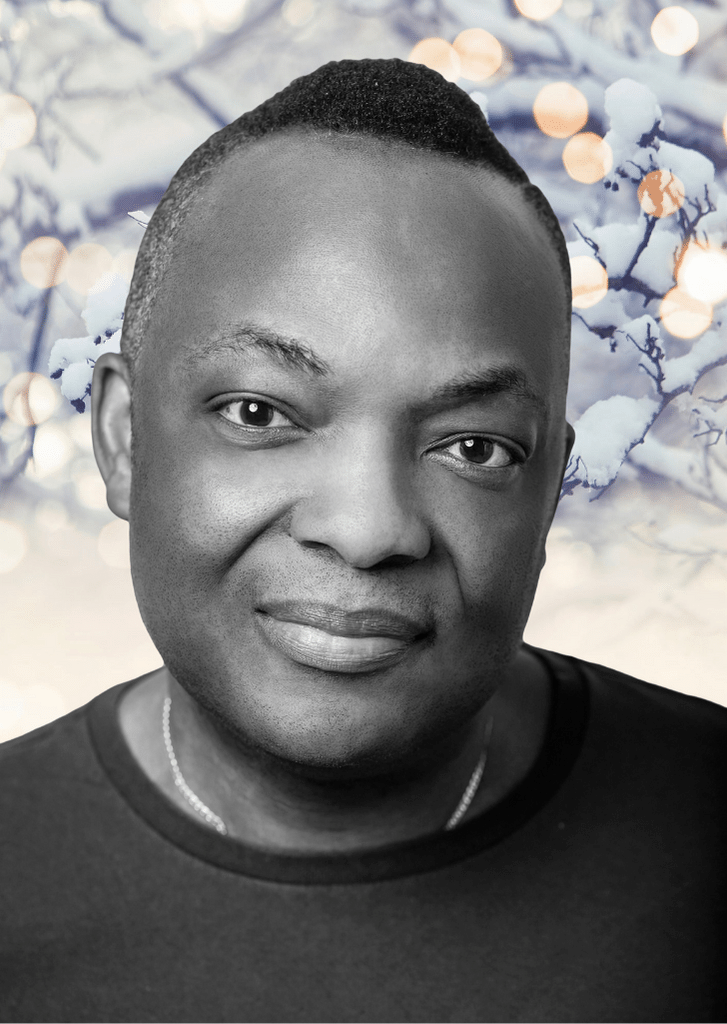

Related article - Uphorial Podcast

What set Clipse apart from their peers was not merely the subject matter—dope, deals, paranoia, betrayal—but the way they dissected it with layered complexity and a nearly literary sense of irony. They didn’t glorify the drug trade; they mythologized its tragic beauty. On Hell Hath No Fury (2006), Clipse's magnum opus, the duo reached narrative and lyrical perfection. Critics hailed it as one of the most complete rap albums of the decade. “This is not just a great hip-hop record,” wrote Pitchfork. “It’s an exorcism.” Tracks like Momma I’m So Sorry and Keys Open Doors offered a masterclass in duality—lavish metaphors cloaked in existential dread. No Malice's conflicted conscience began to emerge: “I’m trying to live righteous, but I’m so raw,” he confessed.

Meanwhile, Pusha T sharpened his cadence into something akin to surgical steel, making every line land like a warning and a flex. By the end of the 2000s, legal disputes with Jive Records, the changing landscape of the industry, and diverging spiritual philosophies pulled Clipse in different directions. No Malice underwent a religious conversion, renouncing the glorification of street life. “I was watching people die, watching people get arrested, watching the same cycles,” he told The Breakfast Club. “I had to step away.” Pusha T, meanwhile, leaned further into the character he’d honed, becoming a solo artist and eventually president of Kanye West’s G.O.O.D. Music. His solo work maintained the Clipse DNA—razor-sharp writing, coke-laced allegories, and a war general’s delivery. But the absence of No Malice's moral foil was palpable. Clipse’s influence stretches far beyond their discography.

The stark, monochromatic aesthetic they pioneered became the blueprint for “luxury drug rap,” influencing everyone from Rick Ross and Freddie Gibbs to Griselda and Tyler, the Creator. Their fashion-forward image—fueled by early ties to BAPE and Pharrell’s Billionaire Boys Club—helped bridge streetwear and high fashion long before it was mainstream. Even the modern trap lexicon owes Clipse a debt. Their intricate slang, coded references, and rhetorical precision made listeners lean in. You didn’t just hear Clipse; you studied them. In recent years, rumors of a Clipse reunion have swirled—fueled in part by their joint appearance on Kanye’s Jesus Is King project and a surprise track on Pusha T’s It’s Almost Dry (2022). While nothing has been confirmed, fans remain hopeful. Not because they want nostalgia, but because Clipse, more than any other act, captured the paradox of rap’s core mythos: pain and triumph, guilt and glory, sin and salvation.