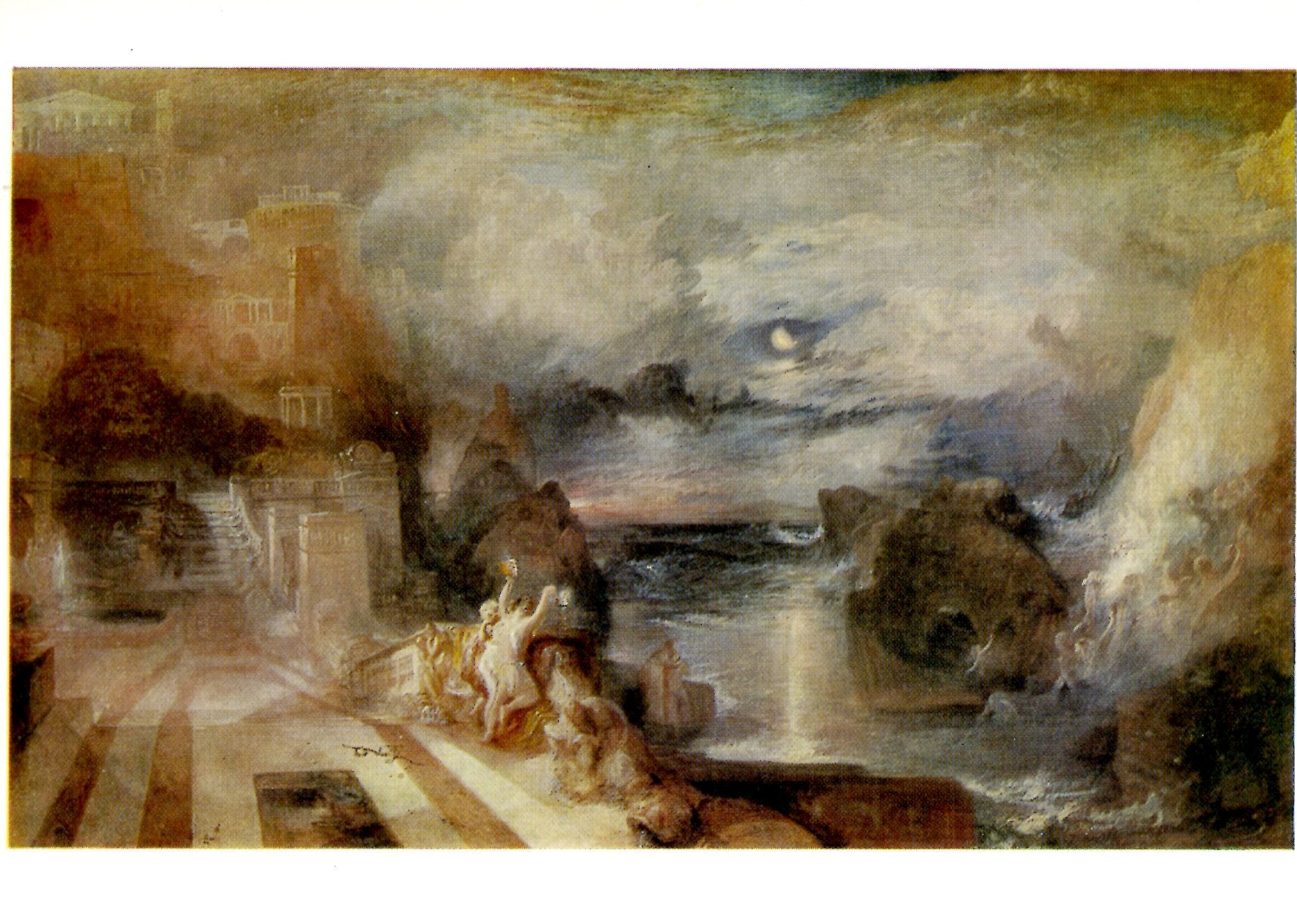

J.M.W. Turner’s 1837 masterpiece, "The Parting of Hero and Leander," stands as a chaotic exploration of the intersection between human passion and the indifferent power of nature. As highlighted by The National Gallery, this dramatic scene depicts the final embrace of Hero, a priestess of Aphrodite, and her lover Leander on the shore just before he begins a fatal attempt to swim across the Hellespont. While the lovers are the narrative focus, they are visually dwarfed by a swirling, turbulent sea and the presence of the gods of love and marriage, symbolizing that the unstoppable force of nature is the true protagonist of the story. The painting even contains ghostly outlines of sea nymphs in the ocean foam, serving as a chilling foreshadowing of the night Hero’s lamp will fail, leading to Leander’s drowning and Hero’s subsequent suicide

Related article - Uphorial Shopify

Stylistically, Turner rejects the rigid order and clarity of the Enlightenment in favor of what poet William Wordsworth described as the "spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings". By utilizing visible brushstrokes and unnatural lighting, Turner prioritized emotional expression over realism, inviting viewers to experience a sense of the "Romantic Sublime"—an artistic approach that uses stormy seas and jagged rocks to inspire a mixture of awe and terror. This intense visual language was heavily influenced by the period's literature, specifically the works of Lord Byron, whose 1813 poem The Bride of Abydos explicitly referenced the same tragic myth. In both Byron’s poetry and Turner’s canvas, the brutality of nature is inextricably linked to the brutality of love, characterizing romantic passion as an inevitable force as powerful and destructive as a tidal wave.

The legacy of this Romantic intensity extends forward to Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel, Wuthering Heights, which The National Gallery identifies as a literary mirror to Turner’s visual art. The connection between these creators is more than thematic; records show that the Brontë sisters copied Turner’s prints as children, and Charlotte Brontë later traveled to London specifically to see his "glowing" and "strange" works in person. Much like Turner used the raging sea to reflect Hero and Leander’s doom, Emily Brontë utilized the bleak and stormy Yorkshire Moors to represent the primal, unruly desires of her characters, Cathy and Heathcliff. When Cathy compares her love for Heathcliff to the "eternal rocks," she is utilizing the same wild natural imagery found in Turner’s stormy landscapes. Ultimately, the enduring power of both the painting and the novel lies in their shared ability to capture the exhilarating and often violent pulse of the human heart through the lens of a hostile natural world.